Last summer a small devaluation in China’s currency, the yuan, was enough to send global markets crashing.

Moreover, expectations of a mild slowdown of its economy caused serious trouble for commodity exporters around the world. One can only shiver when thinking what harm a “hard landing” of the Chinese economy could do to the global economy.

Remember, China is the world’s second largest economy, the world’s biggest trading nation and a great financier of other emerging economies.

Its banking sector is the largest globally; Chinese banking assets are estimated to be equal to 40% of global GDP! Also, its stock markets and its fast growing bond market are among the the world’s largest.

What a load of debt!

Unfortunately, there are signs that China’s economy and banking sector might be in trouble quite soon.

The “recipe” for that appears to be in place.

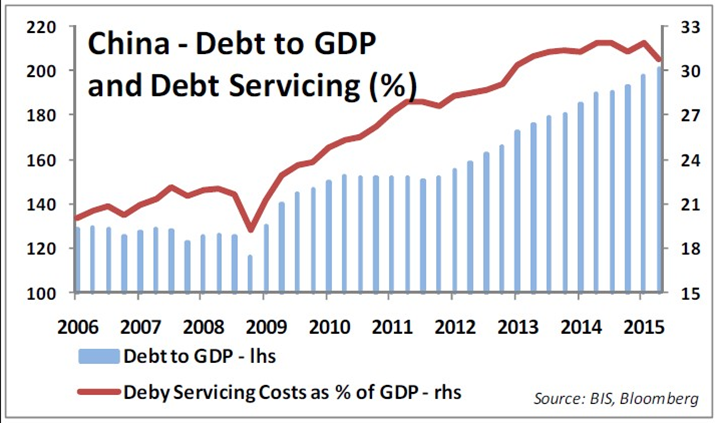

First and foremost, as can be seen from the chart below China’s debt to GDP ratio is currently over 200% (10 years ago it was around 100%), and its debt servicing costs, as a percentage of GDP is around 30%. The key issue of concern here is of course what will happen to asset prices and the real economy when this debt cycle turns sour.

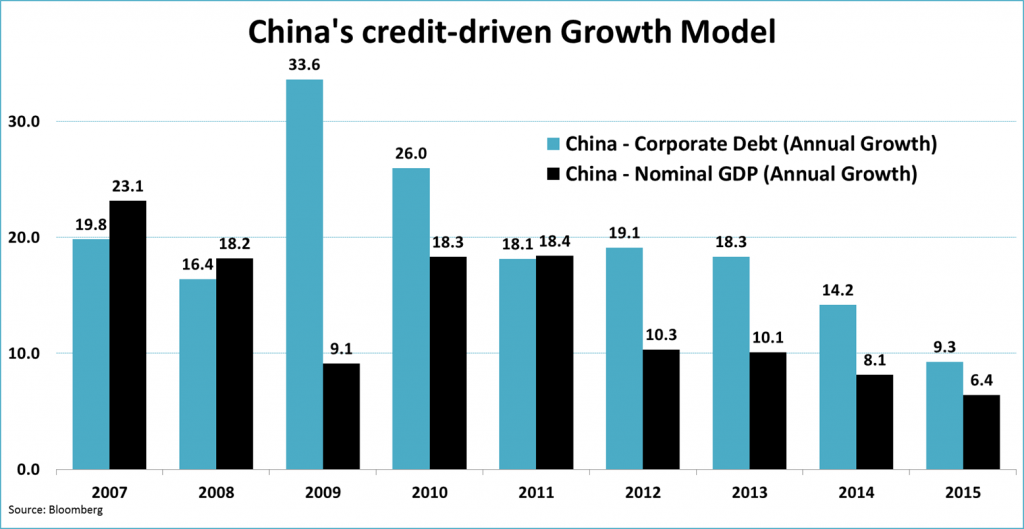

But how and why did this happen in the first place? Well, if we take a careful look at the following chart, we can see that after the global economic crisis and credit crunch of 2007/08, China’s GDP growth was generated through a massive increase in credit granted to the corporate sector. We can also see that, with the exception of 2011, corporate credit growth has been greater than nominal GDP growth every year since the outbreak of the financial crisis. Historically, countries which have experienced such a massive rise in corporate credit have eventually faced serious trouble, think of Thailand in 1997 and Ireland in 2007, to name just two.

What to do with non-performing loans?

The developments mentioned so far are of course directly related to the banking sector, which remember is now bigger than that of the US and the Eurozone.

The prime concern here are non-performing loans (NPLs), that is to say loans which borrowers cannot repay and which, according to The Economist have reached 1,3 trillion yuan (approximately $200 billion)! Given the slower growth of the economy, it is possible that this figure will rise. Key question then is what China will do regarding these NPLs.

Will it downplay the “bad news”, at least for now?

Will it “clean-up” the mess and recapitalize the banks as it did in the nineties?

Or will it let the banks recognise the bad loans and try to find capital themselves?

Surely there is no easy way out. And that is not all; the situation with the banks becomes even more interesting when one considers that probably the majority of loans have gone to firms controlled by the state.

What lurks in the shadows …

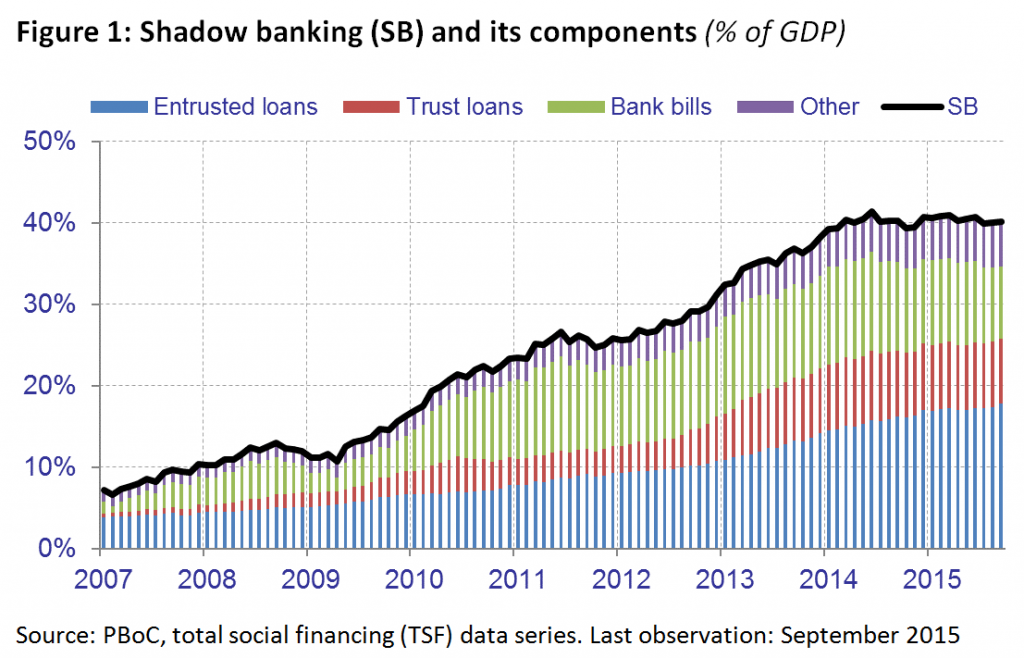

Another issue which must cause concern is the growth of the so-called “shadow banking” system (see chart below); that is to say where borrowers, rejected initially by banks, seek financing.

Typically, the “shadow banking” system is offering high returns in order to attract funds to lend, but as we very well know, high returns are typically accompanied by higher risk!

The crucial point here is that whereas the government provides a guarantee towards bank deposits, “shadow banking” lenders are supposed to stand on their own. This means that they should be taking the necessary steps to manage the higher risk inherent in their activities.

Whether they do that in practice is of course another story.

Again, looking at recent history and the consequences of the rise of the “shadow banking” system in the US prior to the crisis of 2007/08 one can only hold his breath. Of course, the products of China’s shadow system are much less complicated than those in the US but still, what lurks in the shadows – and is big – can be very dangerous.

What about China’s capital markets? Though very large, we should note that investors have limited exposure to them and companies obtain relatively little funding from them; China is still very much a place where banks are the backbone of the financial system. However, surely a country which wants to develop properly must develop sound capital markets. Unfortunately this is not the case.

Wild swings in the stock market

Starting with the stock market, this is often paralleled to a casino. And not without a reason, since it is characterized by wild swings.

For example, in the past year due to the debt-supported buying, blue-chip stocks more than doubled in value only to collapse later on.

What followed was very interesting as state officials panicked and ordered large shareholders to stop selling and state-owned financial institutions to buy.

Not exactly the definition of market efficiency.

Corporate bond issuance goes up but …

Less in the spotlight but equally of concern is the bond market where lately we have seen large increases in the amounts of issued corporate bonds.

According to The Economist, bond issuance in 2015 was 12,5 trillion yuan (approximately $1,9 trillion) versus 7,7 trillion ($1,2 trillion) in 2014. At the same time, and despite the high volume of offerings, spreads between yields on top-rated bonds fell to historic lows, thus implying that market participants “see” a smaller risk of default in those bonds.

One cannot easily reconcile this with a slowing economy! Also, talking about properly functioning markets, it should be noted that regulators in China have yet to accredit the big rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P and Fitch) to provide ratings for bonds issued locally.

It will all come down to the state!

All the issues that we have discussed so far have a common denominator, which is none other than the role of the state in the economy and the financial markets.

As such, by definition, it is the state that needs to show the way forward. It is clear that China needs a better, a more sophisticated financial system. Optimists would point out that over the past 20-30 years when China has been under reform, state officials have managed to identify and timely handle problems.

Furthermore, the fact that the major banks are state-owned, as are the majority of their clients, could also offer some comfort.

Nonetheless, it appears that things might be more challenging this time around as the state needs to manage the following matters simultaneously: a massive debt load; NPLs and the damage that they may do to banks and the economy; and the “shadow banking” system.

And that all must be done sooner than later simply because the longer the reckoning is delayed, the bigger the problems will become and the more severe the consequences.

Big, tough decisions lay ahead …

To do this, the state will have to make big decisions, which, given the past are likely to be very tough.

At the heart of such decisions will lie the fact that, so far, China’s financial system has been built on the assumption that when everything else fails, the “visible hand” of the state will always be there to “correct” things.

It is very unlikely that this assumption can hold forever.

For more finance and business tips, check our finance section and subscribe to our weekly newsletters.

![The 15 best finance websites you should bookmark right now [2025 Edition] alphagamma The 15 best finance websites you should bookmark right now [2025 Edition] entrepreneurship finance opportunities](https://agcdn-1d97e.kxcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/alphagamma-The-15-best-finance-websites-you-should-bookmark-right-now-2025-Edition-entrepreneurship-finance-opportunities-300x350.jpg)